Last day of my tour! I was delighted to meet those of you I met! Thank you for coming! Remember, I have more events coming up in my local area, so I hope to see even more of you. And then, after that, there’s the rest of our lives…

On November 23, 2016, Failed Villain wrote, What about the motivation for an antagonist? They’re always harder for me because I personally have no desire whatsoever to kill someone or rule the world, so I can’t figure out how to express those motivations. Or are they even realistic motivations? Sometimes I get stuck because my villains seem too pure evil. I try to give them some sort of backstory, but again I can’t really relate to that. It’s one thing to write about a character with a dark side, but it’s another to write a character that is pure (or mostly) evil.

I’ve noticed a disturbing side in many of you here on the blog: mrah-ha-ha, you love to write about writing villains! And I love to, too. Does this make us… evil?

Hmm… I’ve selected a few from your pages of excellent responses.

Melissa Mead: Maybe they started with ordinary motivations that got out of hand. For example: “I’m tired of being pushed around. I want some control over this bullying.”

:Punches out bully:

“What a rush! That bully will never bother me again. But there’s this whole gang of bullies…”

:Plan to stop bullies lands the whole gang in the hospital:

“Well, I stopped the bullies, but now the whole town’s mad at me, and I can’t stand it, so…”

And one bad choice leads to another, and another, until the villain’s so caught up in his bad choices that he feels like the whole world’s out to get him, and the only way to make it stop is to rule the world.

Or when he punched the bully, the bully fell and hit his head on a rock, and eventually died, but the villain-to-be was the one who called 911, so no one suspected him. And the next time it was easier to punch harder…

Jenalyn Barton: My favorite villains are the ones that have noble intentions, but go about them the wrong way. Some good examples are Darth Vader (he wanted to save Padme), Light Yagami from Death Note (he wanted to rid the world of evil), Zuko from Avatar: the Last Airbender (he wanted to regain his honor; although he does eventually become a good guy, he starts out as the antagonist), Professor Callaghan from Big Hero 6 (he is bitter over the loss of his daughter and wants revenge). But don’t forget that even the “pure evil” villains have something they want. Captain Hook wants to defeat Peter Pan and get revenge for the hand Peter cut off. Shere Khan hates Man. The Firelord from Avatar: the Last Airbender wants to expand the territory of the Fire Nation. Hans wants to rule his own country. Syndrome from the Incredibles wants to be a superhero. The possibilities are limitless.

StorytellerLizzie: We also hate Old Toad Face because, as it was explained to me once, Voldemort is like a serial killer you hear about on the news: scary but distant. Toad Face is that co-worker that you can’t get to like you, the Manager who gives you extra work because they can, The boss who made you work on Thanksgiving: scary/mean/evil and up close and personal.

I love that, StorytellerLizzie!

Not sure why I’m remembering this, but it seems somehow germane. A fellow children’s book writer once asked me if I would rather be a victim or a perpetrator, if those were the only options. At first, it seemed to me that the only ethical choice was victim, but the more I thought about it, the more I came around to wanting to be the perp. The victim is acted upon, the perp is the actor. Most crucially, the perp gets to pick the crime, which can even be victimless. I can be the perp who decides that my crime is to jaywalk! My crime can be to remove the label from a mattress that you’re warned never to remove!

Suppose my crime is to park my car in front of a fire hydrant and, in a rare tragedy, a fire starts and the fire truck can’t get to the hydrant and people die. Of course I didn’t mean that to happen. How do I move forward? The fault is mine. Do I grow from a perp into a villain?

If the perp isn’t me but a character named Phil, we have the beginnings of a story.

Since Failed Villain asked about motivation, I think this is one that’s easy to get inside. A judge recognizes that Phil didn’t intend to kill people and gives him a mild sentence, say probation and community service. One way–a common way, I believe–our formerly run-of-the mill Phil can turn into a villain is if he doesn’t accept responsibility for what he did–and doesn’t forgive himself, either. These two go together, I believe. We have to accept we did something wrong before we realize there is something to forgive. Maybe since the judge didn’t take his crime seriously, he decides he doesn’t have to–but I don’t think anyone can really disregard an event like this. It burrows inside. It becomes a kernel with a hard shell around it. Tentacles push out from it.

There may be someone on the planet who has never done anything bad or unkind, but I am not that person. Though I’m not a villain, I’ve let a friend or two down. I’ve been thoughtless, rushed, unkind. When memories of these failures bubble up in my mind, I feel awful, and I try not to repeat–but I have to recognize that someday I will. Maybe next time, though, I’ll be better at apologizing or better at making things right, better at taking responsibility immediately. Or not. I’m no world-destroying villain, but neither my acts nor my motivations are always pure.

Back to Phil when he blocked the fire hydrant. Let’s imagine that he has been driving around for twenty minutes looking for a parking spot, and his date is waiting for him, and she’s going to be mad if he’s late again, and his cell phone has died, so he can’t call her.

What can we conclude about him? He runs late, gets people mad at him, doesn’t think ahead sufficiently, doesn’t want people to be mad at him, doesn’t want to face the consequences, tends to do what’s expedient, is perhaps self-centered. He may also have wonderful qualities, be generous, kind to people in trouble, may run late because he can’t refuse to help anyone.

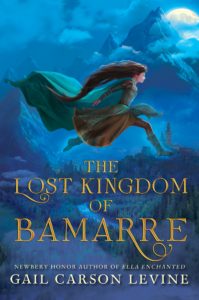

The backstory I provided two paragraphs ago doesn’t go into past trauma or childhood experiences. It’s minimal. We don’t need much back story, if any, for our villains or our other characters, in my opinion. I don’t think I know the back stories for any of my villains. For example, I have no idea why Sir Peter, a minor villain in Ella Enchanted, is so calculating. I sure don’t know what makes Lucinda tick. If it helps us, we can figure out our characters’ pasts, but the reader doesn’t have to see our discoveries unless they come into the story. I don’t even think we need to know or understand our good characters’ motivations, except for our POV’s, whose head we’re in. Back to Lucinda. She ruins people’s lives, not for gain, not really to please them with her gifts. I don’t know why she does it.

Can I find myself in her disastrous gifts? A little. I like to be right as much as she does. I can be a tad impulsive. But I would never ever do any of the horrible things she does, even if I had the power. I can still write her, without knowing why she does anything–or without wanting to ruin people’s lives, too.

As we saw with Phil, our starting point can be the first bad act, whatever it is. As we work out the consequences, we can decide how Phil will respond to them. Through his actions we’ll figure out his personality, which will move us forward into our story’s future with a character who gets more and more complete and real.

When it comes to a purely evil villain, unless we’re writing from her point of view, we don’t have to know her motivation. We have to know only that in a given situation she will go for the worst outcome. Naturally, we do need to know her purpose–what specific harm she hopes to impose and on whom. Our other characters can speculate on her motives and methods so they can come up with strategies to thwart her, but they and we don’t really have to know.

Here are four prompts:

∙ Turn Phil into a villain. List five ways his careless (and selfish) act develops into villainy in his life. Pick one and write a scene or his whole story.

∙ Go the other way and write about Phil coming to terms with what he did and becoming a better person. Make this hard. Have him stumble. If you like, bring in family or friends of one or more of the people to whose death he contributed.

∙ Make Phil’s story really complicated by mixing it up with the circumstances that led to the fire in the house he parked in front of. If you like, a more deliberate villain can have been at work to start the fire. Have Phil get involved.

∙ Expand Phil’s future so that he becomes supremely bad–threaten-the-survival-of-the-universe bad. Write his story along with the story of your MC, who, through small acts of decency, becomes the force for good opposing him.

∙ Take a minor bad characteristic, maybe something that drives you crazy when someone does it. For example, could be tickling people whether they want to be tickled or not. Make it bigger and write a scene or a whole story.

Have fun, and save what you write!