For those of you who are about to dive into NaNoWriMo, all my best wishes! Don’t forget to eat and sleep and read this blog!

I look forward to meeting one–carpelibris!–or more of you this Saturday in Albany, New York!

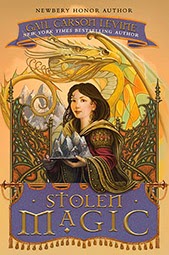

Now, imagine fanfare, a trumpet blowing, confetti. See it first here: the final cover for Stolen Magic!

I think it’s appealing and inviting, just what we want a cover to be.

And on to the post. Two related questions came in over the summer. On July 23, 2014, Elisa wrote, What do you do with parents? I mean, I write from the perspective of children and teens–for the most part–and the things the children/teens do in books these days (you know, saving the world, etc.) are not even remotely possible, most of the time. Kids don’t do that sort of stuff. Plus, since technically our brains haven’t fully developed yet, we wouldn’t have the wisdom to deal with such situations and would need a wise and generally smart, fairly all-knowing adult with us to deal with such things. (Because, from the kid’s perspective, grown-ups know EVERYTHING! Seriously, until I was eleven, I REALLY thought my parents knew basically everything!) So, what to do with the parents, or even grown-ups in general? I know lots of kids in books are orphans, but that’s really cliche, and don’t even get me started on having the kids save the parents, nuh-uh, not even gonna go there, it’s WAY too twisted. I want my parents to be good parents while, at the same time, their kids can do some fairly cool stuff. I can only have them be invalids so often. How do I keep them involved, and not interfering too much, while being really solidly good (also smart, I hate it when the kid is brilliant but the parents are idiots, in real life, the kid would probably be pretty dumb too, you learn from your parents after all) parents?

And on August 19, 2014, Elsabet wrote, What do I do with parents? I really don’t like how uninvolved parents are in literature these days. They’ve all but disappeared! I want the parents in my stories actually BEING there. But them being there means they would cut into the adventures of my kid/teen MCs. How do I work around or through this? Actually, how to I work WITH this? I don’t want the parents to be dumb, or dead, or evil, and I don’t want the kids to be bratty or sneaky. Kids lying to the parents is just not an option. For one, most parents would see through the lies – therefor making it unrealistic – and secondly, I don’t want sneaky, scheming, lying “heroes” in my stories. I don’t like glorifying ugliness. Upon occasion I will have one (scheming liar) as an MC, but only to bring a point across, or to create a contrast. So how do I work this?

The questions generated this from Kenzi Anne: I’ve discovered it’s easier to write parents when they have an actual character. I read the “How To Train Your Dragon” book series a while ago (they are adorable) and I love how the parents are unique individuals with their own characteristics and personalities that actually add to the story– rather than just being the “mom” or the “dad”–there for reality’s sake but not really the story’s. Giving them hopes, dreams, fears, etc. like you would for a main or secondary character might help you to incorporate them better into the story and the plot :). Parents are people too!

Elsabet added: I would like to be accurate, authentic and realistic. Actually, the real reason I want to write parents like this, is because I am modeling them somewhat off of my own parents. My parents are the very best, they really are. And they would do anything to protect their children. They would never be foolish enough to get caught in a situation where they both needed to be rescued at the same time, and if, by some completely random circumstance and several simultaneous coincidences of astronomical oddness they did happen to get into such a situation, they would never wish, or even allow us (their kids) to come to harm by trying to rescue them.

This topic really is a problem for us writers. One of the first laws of children’s literature is that the young protagonist has to solve the story. The parents can’t do the solving or the saving. Readers are asked to suspend their disbelief, big time. Okay, maybe it’s unlikely that a parent needs rescuing or that so many MCs are orphans or that a teen can save the world, but the reader knows this is fiction and, if the story grabs him, he’s happy to go along.

We counter the unlikeliness by developing our situation realistically. Maybe we set the story in a dangerous part of the world. If we’re writing fantasy, we can establish that kidnapping or hostage-taking is common in this kingdom. Then we create a detailed setting and complicated characters and believable characters. The reader may think, I’ve read other stories of parents who need rescuing, but this one is pretty exciting and I’ve never seen it done exactly this way before. And he keeps turning pages. As I think I’ve said before here, there aren’t many possible plots; complete originality is either unattainable or incomprehensible. Even Shakespeare recycled stories from older sources. We take the common elements and reshape them in uncommon ways.

You who know my books are well aware that the only parents I allow on the scene are, ahem, defective. The good ones are either dead or out of the way. In The Wish, Wilma’s mom. a single parent is terrific, but most of the action takes place where she isn’t. So that’s one way–and the true-to-life way I got to be the MC in my own actual growing up. My parents were good people, but they were offstage when I faced most of my challenges: at school, at a friend’s house, in the local park, at the skating rink, in one of the museums I could walk to or get to by bus or subway. (I was lucky to grow up in New York City, where I didn’t need an adult to drive me places.) You can give your characters public transportation to help separate them from grownups.

In Fairest, Aza’s adoptive parents are super caring, but they can’t leave their inn to travel with her to Oscaro’s castle. In their defense, they have no way to anticipate the danger that their daughter will encounter, and, besides, she’s under the protection of a duchess. In A Tale of Two Castles, Elodie’s loving parents send her off to become an apprentice, unaware that the apprenticeship rules have changed. So that’s one strategy: the young MC leaves home for an ordinary reason, but extraordinary things happen, and she can’t go back. The parents, if they know, are wringing their hands, but they can’t rescue their child.

I’m as guilty as any other kids’ book writer of killing off good parents, and I agree that parental mortality is much more common in fiction than out of it, which is fortunate. However, there are orphans in the world. Dave, the orphan I write about in Dave at Night, is loosely based on my father, whose mother died of childbirth complications a few months after having him, and whose father died of (ugh! and gasp!) gangrene when he was about six. I hasten to add that they died a hundred years ago, and medicine has come a long way since then. I doubt that anyone in a developed country dies of gangrene anymore, and death after childbirth is very rare. Interestingly, my father’s stepmother was as bad as Snow White’s. Sometimes life imitates art.

Here are three prompts:

• Your MC’s mom sends her to the corner store for a container of milk. Let’s say she goes reluctantly, because she was in the middle of something, and she isn’t pleasant when they part. On the way, or when she gets to the store, something unanticipated and horrifying happens that makes return impossible. Write what happens in a scene or a story or your NaNoWriMo novel.

• Your MC, Matthea, has great parents, whom she loves and admires. Whenever she has a problem, she discusses it with them, and they always offer great advice. In this story, the advice is good as usual, but following it never seems to work out as planned. Sometimes Matthea flubs when she acts on it, and sometimes the other person doesn’t react as expected. She returns for more advice, which also backfires. Matthea is in a downward spiral. Write the story.

• In the real fairytale, Snow White’s father isn’t around at all. In your version, he is, and he’s kind, and he doesn’t want bad things to happen to his daughter. Include him in the story, but make it all go wrong anyway.

Have fun, and save what you write!